Gilroy, CA— The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and environmental and Indigenous rights advocates are celebrating the final end of the planned mining project at Juristac, following today’s announced acquisition of an additional 2,284 acres of the historic Sargent Ranch property by the Peninsula Open Space Trust. The purchase of the property ensures that the heart of the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape will be protected in perpetuity, in a landmark victory for the Amah Mutsun and the international Indigenous movement to protect sacred places.

“The protection of Juristac is a culmination of more than a decade of work by our Tribe and many dedicated partners, guided by the power of our ancestors who honored this land since time immemorial,” said Amah Mutsun Tribal Chair Ed Ketchum. “Our hearts are full of gratitude for the thousands who stood with us in calling for the sacredness of Juristac to be respected.”

Ceremonial dances and healing rites were held at Juristac for millennia, and the landscape is regarded by the Tribe as a place of great spiritual power. The open space of Sargent Ranch, historically known as Rancho Juristac, is also of regional and statewide environmental importance as a critical landscape linkage that supports the movement of wildlife between the Santa Cruz Mountains and the adjacent Diablo and Gabilan mountain ranges. Today’s Amah Mutsun Tribal Band considers the restoration of their community’s relationship with Juristac as integral to the cultural survival of the Tribe in the 21st century.

“We look forward to coming home to Juristac, coming home to the land where our ancestors walked and prayed,” said Hannah Moreno, a leader of the Amah Mutsun Youth Group. “I see Juristac as a place of culture and connection to land, animals, plants and us humans, being together and thriving.”

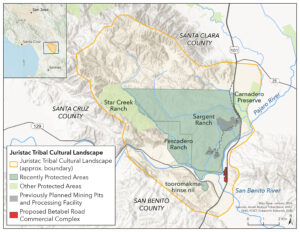

The mine, which was proposed to consist of three massive mining pits, a conveyor belt system, new roads, and a processing facility the size of 46 football fields, would have eliminated hundreds of acres of grassland and oak woodland habitats, irreversibly altering the landscape at Juristac. Sand and gravel processing would have required up to 76,000 gallons of water per day to be pumped from the ground. Erosion, runoff and aquifer drawdown from the mining operations threatened to impair Sargent and Tar Creeks, important tributaries to the Pajaro River.

The Juristac Coalition

The success of the Protect Juristac campaign follows an unprecedented Tribal-led grassroots community movement to oppose the planned mine and advocate for the sacred land to return to Indigenous stewardship. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band steadfastly opposed the mining project since 2016, joining in partnership with the open space advocacy organization Green Foothills and developing a coalition with dozens of environmental, faith-based, human rights, Indigenous rights, and civil rights organizations in an all-out effort to galvanize public support for the protection of the sacred landscape.

“The preservation of Juristac is a testament to the power of this coalition’s advocacy,” Alice Kaufman, Green Foothills’ Policy and Advocacy Director said. “The mining operation would have been incredibly destructive both to the sacred Juristac landscape and to local wildlife. This is an example of what can be accomplished when people stand together.”

The Tribal-led coalition rallied the support of the public in the form of petition signatures, city council resolutions, letters of support from elected officials and community organizations, and a flood of comment letters on Environmental Impact Report for the planned mining project. As a result of these efforts, over 29,000 members of the public signed the Tribe’s petition to protect Juristac, and the city councils of Morgan Hill, Gilroy, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Mountain View, Palo Alto and Sunnyvale all unanimously adopted resolutions to oppose the mine. The Santa Clara County Human Rights Commission, California Democratic Party, and ACLU of Northern California are among an extensive list of agencies, organizations and institutions that authored letters opposing the mine.

After the Amah Mutsun Tribal Council adopted a resolution opposing the mine in 2016 and began speaking out publicly, tribal member and then-UC Santa Cruz undergraduate Julisa Lopez started a Protect Juristac petition in 2017 and the Tribe’s efforts soon snowballed into a highly visible regional movement. The Amah Mutsun hosted a five-mile Prayer Walk for Juristac in 2019, when a group of about 100 tribal members led hundreds of supporters down the streets of San Juan Bautista, ending with a ceremony at the boundary of the threatened land. Another highlight of the campaign was the 2023 Rally for Juristac in San Jose, which brought out around 400 supporters during the public comment period for the mining project’s Environmental Impact Report. All told, Santa Clara County received a record-breaking array of more than 10,000 comment letters opposing the mine and raising a wide array of concerns about its environmental and social impacts.

A Sacred Tribal Landscape

The Sargent Ranch property is located entirely within the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape (see map below), a complex of interconnected Native American sacred sites, village sites and elements such as specific springs, fishing places, ceremonial grounds and landscape features associated with traditional cultural practices. An ethnographic study commissioned by Santa Clara County and summarized in the draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the proposed mining project evaluated the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape as eligible for listing on the California Register of Historical Resources under all four criteria, unequivocally affirming the historical and cultural significance of the area. The EIR also found that the detrimental impacts of the planned mining project on the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape would be significant and unavoidable, even after mitigation.

In Amah Mutsun traditions, Juristac or Huris-tak, which translates to “Place of the Bighead” in the Mutsun language, is home to spirits that are connected with traditional ceremonies. Historically, the tribe’s most revered healers, also known as spiritual doctors, lived at Sargent Ranch and within the greater Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape, conducting healing, renewal, and purification ceremonies there. The Juristac landscape is bisected by earthquake faults and includes the confluence of the Pajaro and San Benito rivers and other unique natural features of cultural importance such as natural tar pits and sulphuric mineral springs.

For countless generations, the ancestors of today’s Amah Mutsun Tribal Band stewarded the landscape of Juristac as they hunted, fished, collected plants for food, craft, and medicine, and lived in small villages. Despite three historic waves of colonization that violently disrupted the continuity of Indigenous lifeways at Juristac, Amah Mutsun people have continually returned to the Juristac landscape and maintained a vibrant oral history of the area.

Following the secularization of Mission San Juan Bautista in 1835, many Mutsun people returned to Juristac, forming small rancherias, growing crops and continuing traditional subsistence practices. However, title to the land was soon unjustly granted to settlers in the Mexican period and then the American period. Ever since the last Tribal people were driven out of the area in the late 1800s, the Amah Mutsun community has had no legal access to the Sargent Ranch property itself, which has been maintained as a private cattle ranch. Despite that, through the 20th century to the present, Tribal members have visited accessible areas along the Pajaro River on the margins of Sargent Ranch, gathering traditional foods and medicinal plants and holding small family gatherings.

The Amah Mutsun Vision for Juristac

“Juristac is a healing place,” Tribal Chairman Ed Ketchum said. “Over time, our people will again discover the medicine that’s in the land. We, the first people, can now forge a path forward where we will be reunited with places we only know through family stories. It’s been over 150 years since a traditional dance was held at Juristac, and we look forward to holding dances there in the future.”

As the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band celebrates the acquisition and preservation of Sargent Ranch, the Tribe looks forward to working with the Peninsula Open Space Trust and other partners on developing long-term plans for the stewardship of the property. For generations, the Tribal community has been unable to access Sargent Ranch, only able to look out across the grasslands over locked gates.

The Amah Mutsun tribal community envisions opening pathways to reconnect with Juristac, bringing back traditional ceremonies, gathering traditional medicines and foods, and engaging in the landscape-scale reintroduction of Indigenous stewardship practices.

“There is a long and hopeful path ahead for the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band at Juristac,” Noelle Chambers, Executive Director of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust (AMLT) said. “AMLT, as a Tribal-led organization, is devoted to ensuring that the Amah Mutsun vision of returning traditional stewardship practices to Juristac is supported and realized.”

The Importance of Juristac for Wildlife

The grasslands, oak woodland, ponds, and freshwater streams of the Sargent Ranch portion of the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape provide vital habitat for threatened species, including the California red-legged frog, California tiger salamander, Central Coast mountain lion, Burrowing Owl, Golden Eagle, and South-Central California Coast steelhead.

“Biologists have long identified the Juristac/Sargent Ranch area as one of the last remaining routes for wildlife to migrate in and out of the Santa Cruz Mountains,” said Julie Hutcheson, Executive Director of Green Foothills. “Preservation of this land is essential to maintain healthy populations of species such as the American badger, mountain lion, and bobcat that need to migrate to find food or mates.”

The health of local wildlife is likewise a matter of concern to the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, for whom native populations of species such as steelhead trout and California red-legged frogs at Juristac are of cultural importance, and an indicator of the health of the land as a whole.

The protection and restoration of large landscapes and critical wildlife linkages such as Sargent Ranch and the greater Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape also support the potential return of locally extirpated native species that, like Mutsun people, have been displaced from these lands. Herds of tule elk, which once ranged north through Juristac into the Watsonville area, are found today along the eastern edge of Mutsun territory in the Diablo Range. California Condors, culturally important messengers between worlds in Mutsun traditions, are documented to have historically occurred at Sargent Ranch before they were pushed to near extinction statewide. California Condor recovery efforts continue, and Sargent Ranch is currently within the Ventana Wildlife Society’s mapped condor range.

Other Portions of the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape Remain at Threat

While the heartland of the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape is now permanently protected through POST’s acquisition of Sargent Ranch and Pescadero Ranch (see map above) other critically important elements of the sacred landscape on private property remain vulnerable to development proposals such as the Betabel Road Commercial Project, which is now a Builder’s Remedy housing development application.

Indeed, the acquisition of Sargent Ranch comes at a time of increasing development pressures within the greater Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape. Other recent proposed major projects within and surrounding the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape in San Benito County include the Strada Verde Innovation Park, San Benito Agricultural Center, Ranch 35 Quarry, and Traveler’s Station project.

Press coverage (will be updated as stories break)

- 2/4/26 Hollister Free Lance: Conservationists buy 2,284 acres of Sargent Ranch property

- 2/2/26 KAZU: Land trust buys 2,300 acres near Gilroy, ending controversial mining proposal

- 2/1/26 SF Gate: ‘Long-sought milestone’: Over 2,000 acres of Bay Area land preserved for $23M

- 1/31/26 KSBW Action News 8: POST protects 2,200-acre Sargent Ranch with Amah Mutsun Tribal Band

- 1/30/26 Mercury News: Watch: Aerial footage of stunning Santa Clara County ranch that sold for $63 million

- 1/30/26 The Real Deal: More Sargent Ranch land sells in latest purchase by environmental trust

- 1/29/26 Hoodline: Peninsula Open Space Trust Secures $23 Million Purchase of Sargent Ranch, Thwarting Quarry Plans and Preserving California Biodiversity and Cultural Heritage

- 1/29/26 SF Chronicle: Land trust buys scenic Bay Area ranch, halting controversial plan for a quarry

- 1/29/26 Mercury News: Palo Alto group buys 2,284 acres at Sargent Ranch, ending 10-year battle over proposed quarry on scenic property

- 1/29/26 Benitolink: (Press Release) Purchase of Sargent Ranch brings end to planned mining project (PDF)

- 1/29/26 Juristac Coalition Press Release: Juristac is Protected: Purchase of Sargent Ranch Brings Final End to Planned Mining Project at Sacred Site (PDF)

- 1/29/26 AMLT Blog: Juristac is Protected!

- 1/29/26 Green Foothills Blog: Great News! Victory at Juristac

- 1/29/26 POST Blog: Protecting Sargent Ranch: A Major Conservation Win in South Santa Clara County

- 1/29/26 POST Press Release: Peninsula Open Space Trust Purchases and Permanently Protects Additional 2,284 Acres of Sargent Ranch